Considering the right waterproofing strategy from the design stage is crucial for the success of below grade projects. However, there is no one right answer.

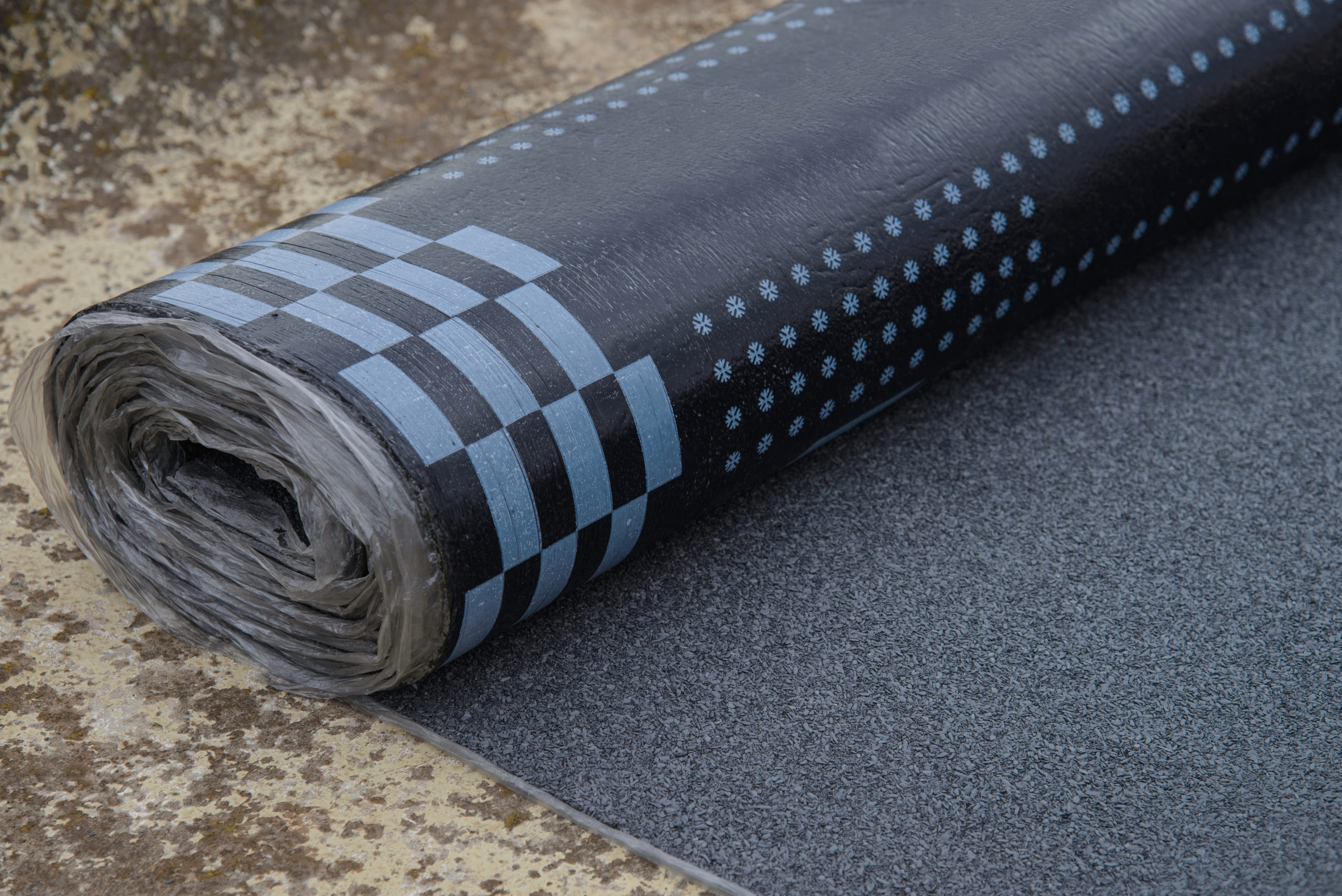

So when faced with this decision, the designer of a project will often start by selecting from several types of external membranes. These include unbonded, fully bonded, and compartmented systems. Each of which will affect the outcome of a project differently.

But no matter their choice, a designer will have many variables to consider.

That can be difficult to navigate. So to help you determine the best strategy for your project needs, let’s look at the factors that affect waterproofing decisions and outcomes and whether there’s a better alternative altogether.

The Factors That Affect the Selection and Outcomes of the Three Membrane Types

Designers typically select one of the three waterproofing membrane types based on the following factors:

Perceived risk of using the systemAccessibility for repairing system defectsQuality control tools of the selected systemOverall cost

Perceived Risk

Out of the three waterproofing membrane categories, there is one that is seen as less risky.

Many View the Use of Fully Bonded Systems as the Reliable Waterproofing Strategy

The idea is that in case of failure, water cannot travel freely between the membrane and structural concrete, so any damage will be localized. That minimizes the cost and scope of the repairs needed.

Despite that big advantage, fully bonded systems also have their drawbacks. They are not flexible when bonded. They cannot bond properly to the structural concrete if not applied properly and in dusty conditions. And most importantly, these bonded systems are thin, making it easy for them to get damaged.

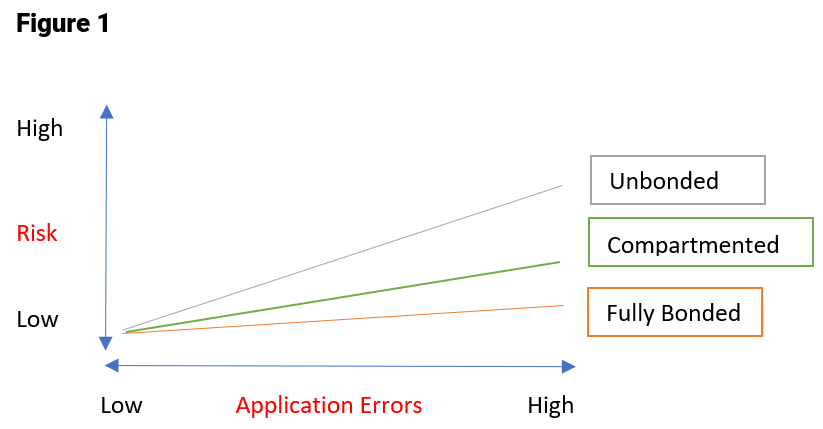

Still, these particular systems tend to remain less risky than others, even when it comes to application errors (see Figure 1).

That Risk Changes, However, When Bad Concreting Practices Are Involved

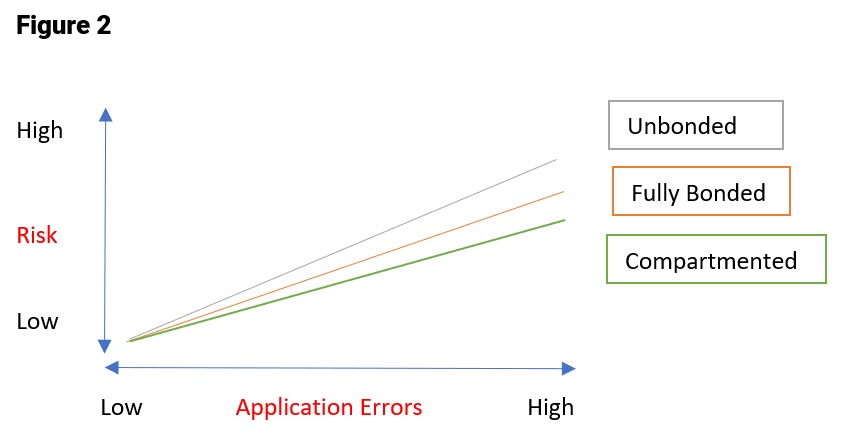

Note how the dynamics change with bad concreting practices. The risk associated with application errors deviates as follows (see Figure 2).

In this scenario, the bond between the membrane and structural concrete would have been compromised. Once that occurs, a fully bonded system will become riskier than a compartmented system due to the following reasons (among others):

Membranes in fully bonded systems tend to be thinner than ones in compartmented systemsThey don’t have horizontal and vertical protection as many compartmented systems doThey also do not have the same reactive system for repairs with flanges in each compartment

No matter the system, however, the risk related to application errors is shown as much steeper (as seen in Figure 2) when there are bad concreting practices involved. You need only compare the risk to a project with good concreting practices to see the significant impact (as shown in Figure 1).

ccessibility for Repairing System Defects

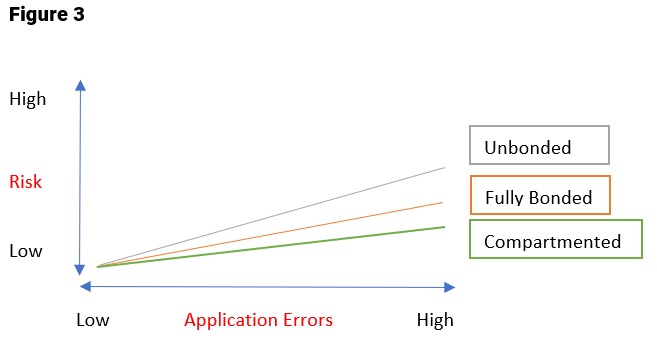

For stakeholders who prefer a waterproofing system that workers can access for repairs if something does go wrong, compartmented systems are perceived as the best (see Figure 3).

Why is that the case?

It’s mainly because it is possible to attempt to repair each leaking compartment of the system with injection flanges.

As for the other waterproofing systems, the unbonded one remains the riskiest, as it would be very hard to determine the source of its leakages.

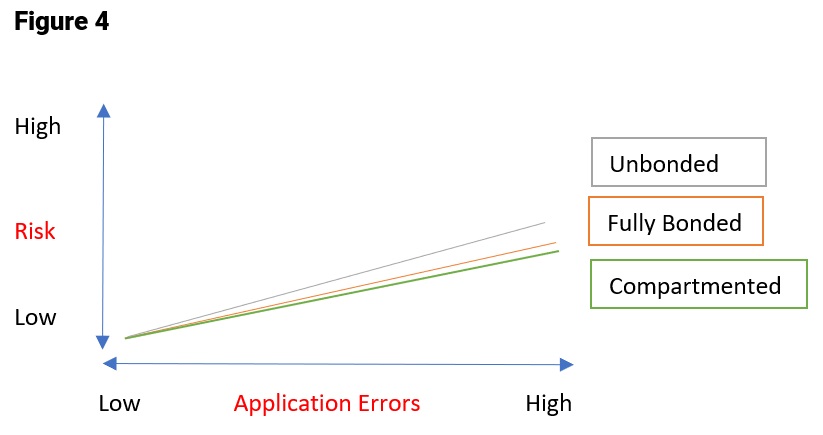

Again, what adds to the complexity of just selecting the best perceived waterproofing system is a poor concreting application.

In this case, combining a poor concreting application with a compartmented system means water is more likely to migrate between compartments. That will increase the risk of the compartmented system’s waterstops not bonding adequately to the structural concrete. At the same time, isolating individual compartments in the system and repairing them with flanges will become less effective, since the water will be migrating between adjacent compartments. And that leads to a change in risk assessment (as seen in Figure 4).

Quality Control Tools

For stakeholders who depend on quality control tools to ensure that a membrane is installed properly, a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) compartmented system might be more appealing. Usually coming with the desired quality control tools, it has an edge over most types of fully bonded and unbonded systems.

The quality control tools that a PVC compartmented system typically comes with include a double-wedge welding of membrane overlaps. And that’s followed by pressure testing to guarantee that the overlap is properly welded.

Other quality testing measures for the overlaps in this case might include vacuum testing and spark testing.

All the above are great tools in theory. However, this quality control edge tends to be more theoretical than realistic in many instances. Such instances include (but are not limited to) vertical membrane applications. After all, it would be very unpractical to make a double-wedge welding joint and test each individual joint in vertical (or otherwise complicated) applications.

Overall Cost

Cost per system is not universal and differs in each market. But in general, an unbonded system is the cheapest, while fully bonded and compartmented systems tend to be more expensive.

However, when we consider what I call the membrane system lifetime value, cost assessment tends to be more complicated. The lifetime cost would include the initial cost of the system, the expected life of the system, and repair costs of the membrane over the service life of the structure. Once again, concreting practices play an important role with the associated costs of repair and replacement. Choosing a waterproofing system based on cost is therefore a complex decision that includes many variables, which are hard to quantify.

Why Concreting Adds Complexity to These Factors

Waterproofing is an interconnected network of activities. So rationally selecting the appropriate system depends on many variables. A common variable that adds to the complexity of the selection and on the consequences associated with that selection is the quality of the concrete. That in turn is a function of the structure’s concrete mix and application. Therefore, it is impossible to assess the performance of the waterproofing membrane system in isolation without considering the concrete’s quality.

How to Simplify and Improve a Waterproofing Strategy with a Fourth Alternative

The fourth alternative is not a compromise between an unbonded, fully bonded, or compartmented system. A fourth alternative is a better waterproofing strategy. It’s a waterproofing solution that simplifies a designer’s choice while providing more predictable outcomes.

Simply put, the fourth alternative is to design and construct a waterproof structure that can sustain itself without external protection. That eliminates the concern of that external protection defecting or failing, as it transforms the concrete itself into a solid waterproof barrier. It also minimizes the need for extra labor or application time, as there is no membrane to install.

But how is this waterproofing strategy possible? What makes it work?

It all functions off the following principles.

The Structure Should Be Waterproof for Its Entire Intended Service Life

This is attained by using quality concrete, proper jointing systems, and adequate reinforcement.

The latter follows conventional construction methods, so let’s focus on those first two aspects.

To obtain quality concrete in this case, builders need to ensure that they use a suitable mix that is permanently waterproof. An easy way to do this is by applying a reactive waterproofing admixture, such as Kryton’s Krystol Internal Membrane

(KIM), with the established best practices for mixing, placing, and curing concrete.

Once added directly into the concrete, KIM disperses Krystol technology throughout the concrete mix, which remains dormant until water is nearby. When in the presence of water, the chemical technology reacts, forming interlocking crystals to block pathways for water in the concrete. That reduces the concrete’s permeability, shrinkage, and cracking. It also improves the concrete’s ability to self-seal for the rest of the structure’s life span.

But what about proper jointing systems?

Special consideration should be given to jointing details, including construction, expansion, and control joints. Using a combination of physical and chemical barriers is recommended for long-term performance. A good example of this is the Krystol Waterstop System. It offers three levels of protection for all jointing details. Depending on the level of protection chosen, the system might make use of two types of waterstops (one for sealing joints and one for crack control), a crystalline slurry that uses Krystol technology for concrete joints, and a crystalline grout.

For Extra Reliability, Designers Need to Determine a Suitable Repair Strategy

With a reliable waterproofing admixture and jointing protection system, a concrete structure should be quite safe.

But it’s important to include redundancies into a waterproofing system. It’s what gives a structure extra protection in case the situation does not go as planned. But to include those redundancies, designers need to consider a suitable repair strategy.

The repair strategy should be based on durable materials that are compatible with concrete. It should not be cosmetic and planned for the short term as it has to be able to fix the problem at its source. Otherwise, the problem will remain present, causing more damage in the long run.

dditional Protection Needs to Be Considered When Handling Projects That Are Considered High-Risk

These can include liveable basements, museums, and other structures where the cost of repairs is very high.

If that is the case for a project, a designer could add a membrane system to the waterproof structure. Selecting one will depend on the previously mentioned factors. But in general, as discussed earlier, the quality of concreting practices will affect how well a membrane type will perform. So it’s important to maintain good concreting practices no matter which type of waterproofing membrane system is chosen.

In short, the fourth alternative is a waterproofing strategy that fundamentally relies on a self-sustained waterproof structure free of application and additional labor concerns, a suitable repair strategy, and when necessary, the extra protection of a waterproofing membrane system.

The post Choosing a Waterproofing Strategy for Below Grade Applications: A Fourth Alternative appeared first on Kryton.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.bellanovatravel.net/?p=204